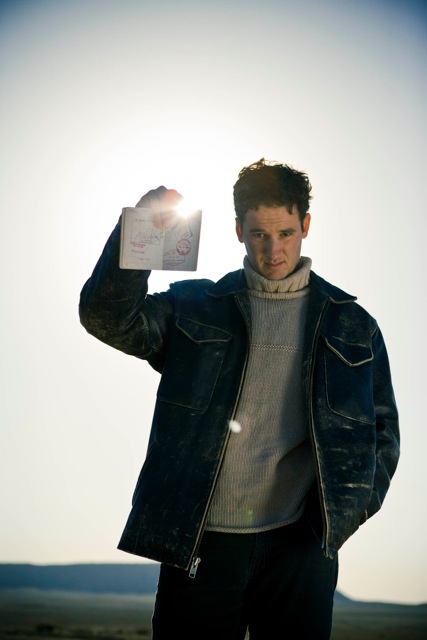

JAKE HALPERN

Biography

We all have at least two versions of who we really are. Here are mine...

We all have at least two versions of who we really are. Here are mine...

Photography by Gregory Halpern

Jake Halpern is a journalist, bestselling author, and the winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize. His first book, Braving Home (2003), was a main selection for the Book of the Month Club by Bill Bryson. His nonfiction book on debt collectors, Bad Paper (2014), was excerpted as a cover story for the New York Times Magazine. It was chosen as an Amazon "Book of the Year" and was a New York Times best seller. His acclaimed book on refugees, Welcome to the New World (2020), expanded his Pulitzer-winning series in the Times; it was selected as one of the best books of the year by the New York Times and The Guardian. Jake’s debut work of fiction, a young adult trilogy, Dormia (2009), has been hailed by the American Library Association's Booklist as a worthy heir to the Harry Potter series. His more recent young adult novel, Nightfall (2015), was a New York Times best seller.

As a journalist, Jake has written for The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, The Wall Street Journal, Sports Illustrated, The New Republic, Slate, Smithsonian, Entertainment Weekly, Outside, New York Magazine, and other publications. In the realm of radio, Jake is a contributor to NPR's All Things Considered and This American Life. Jake's hour-long radio story, "Switched at Birth," is on This American Life's "short list" as one of its top shows of all time. Last, but not least, Jake is a fellow of Morse College at Yale University, where he teaches a class on writing. He recently returned from India where he was visiting as a Fulbright Scholar.

Photography by Jen Judge

When I was twenty years old, I took some time off from college and moved to Prague. It was the sort of inspired, half-baked decision that you can only make when you are twenty and clueless. A few weeks into my stay in Prague, I found an apartment and settled into a routine of doing very little – wandering around the city, reading, and living off the money I'd saved. Almost immediately I sensed that it was a special time to be living there. This was back in 1995, and the city was teeming with artists, expatriates and lingering tourists, living in two-dollar-a-night hostels. Everyone there was writing a novel, or a play, or at least some essays. The apartment that I took over – a drafty subterranean vault beneath a neighborhood pub – had been the home of a long string of expatriated Americans before me, and the closets were filled with an array of dusty, discarded and abandoned manuscripts, most of them uncompleted.

Eventually, I got swept up in the bohemian spirit of it all and set to work on piece of writing of my own, a screenplay to be precise. The screenplay, which was called the Papaya Trap, was about a con artist who falls in love with a beautiful one-armed girl. The truly transformative event of my time in Prague, however, was my decision to investigate my family's roots in this part of the world. I knew that some of my ancestors had once lived in Prague, and on a whim I telephoned my great-uncle (Joe Garray) in America, and asked him if we had any relatives who were still here. "No they all perished in the Holocaust," he said. But I kept pushing him and eventually he told me that the man who saved him from the Nazis still lived in a farm house in Slovakia at the edge of the Tatra Mountains. A week later I took a commuter plane to Bratislava and then a train to the small town where this man lived.

I showed up at his door after sundown and he came to the gate cautiously, leaning heavily on a wooden cane, face trembling and bald except for a few long loops of white hairs, his feet engulfed in a swarm of mutts who guarded his every step. He led me through the back door and into his kitchen. It was a bare room, illuminated in dingy fluorescent light, occupied only by a few stools, a couch covered in dog hairs, and a hissing radiator. Here he told me about hiding my uncle and their numerous close calls with the Slovak Gestapo. When the situation at the farmhouse became too heated, they fled to the mountains in the cold of winter and lived like hermits for six months.

I was deeply moved by this story and I ultimately spent the next two years turning it into a short film called Ani Mamim, which is now part of the National Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C. More than anything else this story convinced me that I wanted to dedicate my life to becoming a professional storyteller. This quickly proved difficult – especially when it came to paying the rent – and I was soon working for the man.

After graduating from Yale in 1997, I found myself in a Boston high-rise, cramped in a desk-length cubicle, shirt pressed and starched, summarizing court decisions on insurance law. I can't remember exactly when I realized I had to get the hell out of there, very early on I think, probably around the time I was scolded for hanging a "visually jarring tie" on my coat-rack. I began to feel that I was being watched incessantly; and ultimately, it was this totalitarian, Kafka-esque creepiness that impelled me to leave the job, and as if that weren't enough, the country too.

I set off to Israel where I worked as a writing tutor at the American International School near Tel Aviv. In my spare time, I worked as a freelance journalist. The first piece that I got published appeared in Commonweal in 1998. It chronicled my visit to Hebron in the West Bank – a place infused with a strange mix of religious fundamentalism and Wild West gun-slinging – where Hamas gunman stood poised on street corners as orthodox Jews walked past with holsters and pistols on their belts. As disturbing as all of this was, it was a hell of a lot more interesting than my cubicle back in Boston, and I soon became convinced that I wanted to become a journalist.

After returning from Israel, I landed an internship at The New Republic. My co-workers here were a mix of policy wonks, art critics, and political junkies. I was none of these, and instead of trying to pass as one, I set out to write a different kind of story; yet every time I did, it ended up being about some wild and often hellish place, inhabited by a handful of stalwarts who refused to leave. I became a specialist on burning towns, flood plains, and hurricane islands.

My chief responsibility at the magazine was researching and fact-checking. I spent hours, days, and weeks looking for correct spellings and exact dates. Being a quick fact-checker was always a point of pride among the office grunts like myself, and though it was an obscure and largely useless skill, I found it quite helpful in tracking down information on dangerous and outlandish towns. On my lunch breaks and in between assignments I searched for clues, and gradually I found them – reports of holdouts living on lava fields, windswept sandbars, and desolate arctic glaciers. I spent Sunday afternoons combing the web with a smattering of search terms like “squatter,” “won't leave home,” and “people call him crazy.” I became friendly with the press office at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and I pumped them for ideas. It turned into something of a hobby. Some people collected stamps, others pressed leaves, I scavenged for strange and daring homes. Eventually, the short magazine pieces that I wrote on people and their homes attracted the interest of a literary agent who convinced me to write a book, which I then did. This book – Braving Home (Houghton Mifflin, 2003) – allowed me to quit my job and become a full time, self-employed writer.

While I was working on Braving Home, I carried a digital audio recorder, which allowed me to capture all of my encounters with “broadcast quality” recordings. With the help of my friend, Ted Gesing, I was able to turn these recordings into a five part series on National Public Radio's All Things Considered (Weekend Edition). I loved doing this work for NPR and I have gone on to become a contributor to All Things Considered (Weekday) and This American Life. The other cool byproduct of writing Braving Home was that I began receiving commissions to do journalistic pieces for publications like the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, and the Wall Street Journal.

In the years since then, I got married and became a father. I have two sons. We often travel as a family. In 2011, we all moved to India and spent a year there. My wife, who is a doctor, got a grant from the National Institute of Health and I won a Fulbright. But really we were just craving a bit of adventure.

At the time, I was tired of the workaday routine of my life – going to Costco, working out at the gym, passing out at night watching “The Wire” on my iPad. I was tired of picking up my little kids at daycare at precisely 5 PM, checking an excel spreadsheet to see how many bowel movements they made per hour, and then putting down my initials, my approval, as if to say: yes, marvelous, all is well, all is how it should be. I was tired of living a sensible, orderly life governed by rational decisions. I wanted to be back in India, where the priests beat the gongs in the temples with relentless fury, as if to say: wake up you comatose fool, be here, right now, before your life passes you by. Looking back, it seems like a romantic and somewhat clichéd notion. But at the time, I assure you, I was very earnestly itching to get the hell out of dodge.

When we returned from India, I dedicated myself — in earnest — to writing books, which proved to be a far lonelier endeavor than I ever imagined. On winter mornings, once the kids were off to school, and my wife was gone to work, the stillness of the house was unnerving. I sometimes stared out the window and watched the snow fall as my coffee went cold. Progress often seemed impossibly slow (352 words today, 456 words the day after) and, perhaps inevitably, self-doubt took hold and seemed to metastasize. Who are you kidding?

One saving grace was teaching. I began teaching writing at Yale, the very place where I had once been a student. The first time I walked into a classroom I felt such a fraud that I half expected to be laughed out of the room. You? Seriously? In my mind, I was still a public-school boy from Buffalo – a Jew from the Rust Belt doing his best to feign a sense of belonging amidst the prep schoolers, who spoke casually of boathouses and regattas and summers in Martha’s Vineyard. But the students in my classroom saw me – not as the brash boy I’d once been – but as the seemingly, serious young man I’d become. And so, I kept teaching and kept writing.

In 2016, at the age of forty-one, I began what would become the most challenging and defining project of my career. It was a comic. A nonfiction comic. The idea, itself, was not mine. It came from a very shrewd editor at the New York Times named Bruce Headlam. His idea was to create a “graphic narrative,” which chronicled the experience of a refugee family in the United States, after it had arrived. The hope was to create a project that resembled Maus or Persepolis, but which was serialized in The New York Times, in a weekly or biweekly basis. I soon teamed up the illustrator, Michael Sloan, and we began charting a path forward.

Our immediate challenge was finding a family to profile. I contacted my friend, Chris George, who runs IRIS, a refugee-resettlement agency here in Connecticut. Chris suggested that I identify and chronicle a family’s story from the very day they arrived; in other words, I would be there at the airport or at the bus terminal, when they first showed up, and would follow them around, more or less, indefinitely. A short while later, Chris called me up and announced, “I may have found your family!” As it turned out, there were two brothers – Issa and Ibrahim – each of whom was arriving with their respective families, on Election Day 2016.

So, on Election Day, Michael and I went to meet the two families. We said a quick hello, but mainly, we simply watched as the families arrived here in New Haven, CT. The next morning, I awoke to the startling news that Donald Trump had just won the presidency; immediately, I thought of these two families. It occurred to me that they had landed in one country and then woken up, the next morning, in another.

For the next three years, Michael and I followed these two families. We chronicled their lives in the New York Times and, later on, expanded this series in the form of a book. Our series in the Times ended up winning the Pulitzer Prize. The project was hugely meaningful to me and in so many ways, Ibrahim and Issa, reminded me of my great uncle, Joe Garray, and his story. As a story teller, it seemed, I had come full circle.

Nowadays, I divide my time between producing podcasts, doing magazine articles, and writing books. And the books aren’t all nonfiction. I have a several fantasy series for young adults that I write with my friend, Peter Kujawinski. When I'm not working, I enjoy traveling to remote places and hiking in the woods with my wife, my two sons, and our 100-pound golden retriever, Milo.